This Is the Echidna Penis. I Echid You Not.

Posted: February 7, 2012 Filed under: Animal Penises | Tags: echidna, hemipenis, Hydra, mythology, penis, profound feelings of loss, snake, spiny anteater 3 CommentsThe short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus acelatus), also called the spiny anteater, is one of those bizarre half mammal half reptile Franken-animals from down under known as monotremes, an order whose more familiar representative is the duck-billed platypus.

In Greek mythology, Echidna was a half nymph half snake monstress, the mother of the fearsome Chimera, Hydra, Gorgon, and countless other creatures in the Greek pantheon. That this she-beast is the namesake of the humble and sometimes adorable short-beaked echidna may seem unfair, but this, dear reader, is only because you are unfamiliar with its great and awful penis.

I warn you: the following video is not for the faint of heart. Better persons than I have been unraveled by what are about to see, some very dear to me. But they did not understand the burden of this profession, that as penile scientists we must accept the sublime with the terrible, often at the same time. Now prepare yourself, and,

Behold, the four-headed Hydra birthed from the belly of Echidna!

So now after watching the video five or six times in a row, agape and speechless, your trembling awe finally subsiding, you may ask aloud in a quaking voice, “Why, oh God, why is it like this?” To answer this we must abandon Mythology and give ourselves over to Science.

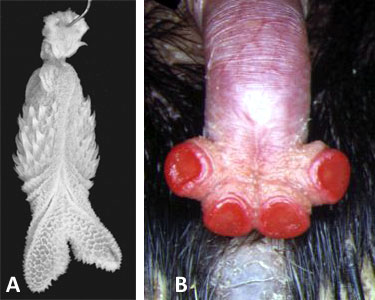

The reason the echidna’s penis is so unusual has to do with its reptilian evolutionary heritage. Male reptiles typically have a pair of penes, known as hemipenes, only one of which is used during copulation. Additionally, some hemipenes fork at the tip, for a total of four penile prongs (see fig. 1a). Echidnas seems to have inherited precisely this style of doubly bifurcated reptile penis, but fused into a single mammal-like penile shaft (fig. 1b).

Fig. 1: (a) Single forked hemipenis of the snake Atractus attenuatus (Meyers and Schargel, 2006). (b) Echidna penis

The mystery does not end here: for many years scientists were stumped by the fact that the male’s penis has four prongs but the female’s genital tract only has room for two. Then, in one of those serendipitous occurrences that drive science forward, reproductive biologist Dr. Steve Johnston from University of Queensland and his colleagues inherited an unusually gregarious echidna who had been retired from a zoo for displaying erections during public viewing sessions (New Scientist, 2007).

What Dr. Johnston discovered was that, just how reptiles only use one hemipenis at a time, male echidnas disengage one side of their penis and only use half when ejaculating (Johnston, 2007). Those of you with a discerning eye might have spotted this towards the end of the above video; see also fig. 2.

I salute you, Dr. Johnston, not only for your solving the prong puzzle, but your breezy smile here seems to indicate that you, like I, have come to peace with the burden scientists like us must endure. I hope this means that you, unlike I, can still salvage those connections you share with the people most important to you. Yes, it’s clear from that smile, you have a family that loves you and understands your passion for your work. You are the man who has it all.

References

ABC Science. 2000. Echidna love trains [online].

Johnston, S. D., Smith, B., Pyne, M., Stenzel, D. and Holt, W.V. 2007. One‐Sided Ejaculation of Echidna Sperm Bundles. The American Naturalist, 170 (6): E162-E164. [pdf]

Myers, C. W. and Schargel, W.E. 2006. Morphological Extremes—Two New Snakes of the Genus Atractus from Northwestern South America. American Museum Novitates, 3532:1-1. [pdf].

New Scientist. 2007. Exhibitionist spiny anteater reveals bizarre penis [online].

[…] far this blog has mostly been concerned with the first aim, such as in the echidna penis article, and we’ve touched on the third aim in the barbed penis article. But today I would like to […]

Despite much googling, I cannot find an answer to my urgent question, which I was very much hoping your post would address, but it did not (but I liked it anyway!), and that is: Why did reptiles evolve the basic hemipenis in the first place? What makes them need two? Let alone the forked version? What advantage does this give them? (By the way, this blog is amazing. Finding such treasures is why I love the internet.)

Fascinating question, Joanna! Researchers believe that the dual hemipenes configuration in reptiles and snakes is an inherited feature from their aquatic evolutionary ancestors whose reproductive structures were genetically coupled with a certain pair of bilaterally symmetric clasper fins. Paleontologist John A. Long explains:

“So initially, the reproductive structures of early jawed fishes were paired as part of the leg or hind-limb pattern of bones. After paired fins had transformed into legs, the claspers were lost, but in their place, other paired reproductive structures merged from the urogenital plate, such as the hemipenes of lizards and snakes. In subsequent evolutionary radiations, the paired units were unnecessary (because only one mating organ is needed to do the job properly), so the loss of one side meant that the single penis emerged, so to speak, as the dominant male reproductive organ in higher vertebrates.”

From: http://www.thisviewoflife.com/index.php/magazine/articles/dawn-of-the-deed-part-3-from-clasper-to-penis-weve-come-a-long-way-baby

So the short answer might be: evolutionary inertia. However, in some situations two penises might also be an evolutionary advantage over one, which might explain why the dual arrangement still exists in modern species. For instance, certain snakes are known to alternate between hemipenes when mating multiple times within a short time-frame. Researchers have shown this allows the snake transfer more sperm than if it were to use one hemipenis only, because each hemipenis is connected to an independent reproductive tract with its own (limited) sperm production capabilities. In other words, much like a double-barreled shotgun, the snake’s two hemipenes allow it to cut down on “reloading time”, conferring a reproductive advantage over a single-barreled hemipenis.

Stay Curious,

Dr. Richard Cox, PhD.